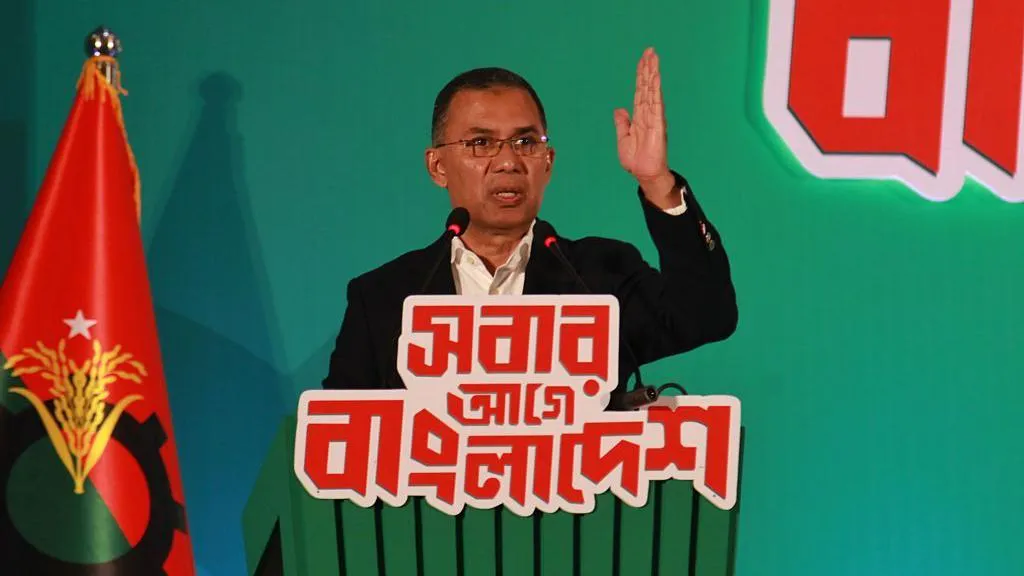

Tarique Rahman has signalled that Bangladesh will chart its course independent of both India and Pakistan

Tarique Rahman has signalled that Bangladesh will chart its course independent of both India and Pakistan

When the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) swept to a landslide in the general elections on Friday, Delhi responded with studied warmth.

In a message posted in Bengali, Prime Minister Narendra Modi congratulated BNP leader Tarique Rahman, the 60-year-old dynast, on a "decisive victory". He pledged India's support for a "democratic, progressive and inclusive" neighbour. He added that he looked forward to working closely to strengthen "our multifaceted relationship".

The tone was forward-looking - and careful. Since Sheikh Hasina fled to India after the Gen Z-led July 2024 uprising, ties between the neighbours have frayed, with mistrust hardening on both sides. Hasina's Awami League - the country's oldest party - was barred from contesting the election.

Many Bangladeshis fault Delhi for backing an increasingly authoritarian Hasina - a grievance layered atop older complaints over border killings, water disputes, trade curbs and incendiary rhetoric. Visa services are largely suspended, cross-border trains and buses halted, and flights between Dhaka and Delhi sharply reduced.

For Delhi, the question is not whether to engage a BNP government - but how: securing its red lines on insurgency and extremism while cooling rhetoric that has turned Bangladesh into a domestic political talking-point.

A reset is possible, say analysts. But it will require restraint - and reciprocity.

"The BNP, the most politically experienced and moderate of the parties in the fray, is India's safest bet moving forward. The question remains: how will Rahman govern the country? He is clearly seeking to stabilise India-Bangladesh ties. But this is easier said than done," says Avinash Paliwal, who teaches politics and international studies at SOAS University of London.

Sheikh Hasina, seen here at a 2022 reception with Indian PM Narendra Modi, now lives in exile in Delhi

Sheikh Hasina, seen here at a 2022 reception with Indian PM Narendra Modi, now lives in exile in Delhi

For Delhi, the BNP is not an unknown entity.

When the party - under Rahman's mother Khaleda Zia - returned to power in 2001 in coalition with the Islamist Jamaat-e-Islami, ties with India cooled quickly. The BNP-Jamaat years were marked by turbulence and deep mutual mistrust.

Despite early courtesies - India's then national security adviser Brajesh Mishra was the first foreign dignitary to congratulate Khaleda Zia - trust proved thin. The apparent ease with which the BNP maintained relations with Washington, Beijing and Islamabad fed Delhi's suspicion that Dhaka was drifting strategically.

Two Indian red lines were soon tested: curbing support for north-eastern insurgents and protecting Hindu minorities.

Post-election attacks on Hindus in districts such as Bhola and Jessore alarmed Delhi. More damaging was the April 2004 seizure of 10 truckloads of weapons in Chittagong - the largest arms haul in Bangladesh's history - allegedly destined for Indian rebel groups. Economic ties fared little better. A proposed $3bn investment by Tata Group stalled over gas pricing and collapsed in 2008.

Ties kept deteriorating. In 2014, Zia - then in opposition - cancelled a scheduled meeting with then Indian president Pranab Mukherjee, citing security concerns, in what was widely seen as a snub to Delhi.

That uneasy history helps explain why India later invested so heavily in Sheikh Hasina.

In her 15 years in power, Hasina delivered what Delhi prizes most in its neighbourhood: security co-operation against insurgents, improved connectivity and a government broadly aligned with India rather than China - a partnership as strategically valuable as it was politically costly.

India and Bangladesh share a 4,096km (2,545-mile) border

India and Bangladesh share a 4,096km (2,545-mile) border

Now living in exile in Delhi, she faces a death sentence in absentia over the 2024 security crackdown - violence in which the UN says about 1,400 people were killed, most by security forces. India's refusal to extradite her has further complicated an already fraught reset with Dhaka.

Last month, Foreign Minister S Jaishankar travelled to Dhaka for Zia's funeral and used the occasion to meet Rahman. At a recent rally, the BNP leader declared: "Not Dilli, not Pindi - Bangladesh before everything," signalling independence from Delhi and Pakistan's military headquarters in Rawalpindi.

Pakistan - India's nuclear-armed arch rival that was defeated in 1971 to secure Bangladesh's independence - remains a central, if sensitive, factor in the equation.

After Hasina's fall, Dhaka wasted little time in mending fences with Islamabad. A direct Dhaka-Karachi flight resumed last month after a 14-year hiatus. Earlier, there was a first visit by a Pakistani foreign minister to Bangladesh in 13 years. Senior military officials have exchanged trips, security co-operation is back on the table, and trade climbed 27% in 2024-25.

The optics are unmistakable: a once-frosty relationship has thawed.

"What concerns us is not that Bangladesh has ties with Pakistan - as a sovereign country, it is entitled to," Smruti Pattanaik of the Delhi-based Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, told the BBC. "What was unusual was the near absence of engagement during Hasina's tenure. The pendulum had swung too far in one direction; now it risks swinging too far in the other."

Direct flights between Bangladesh and Pakistan resumed after more than a decade

Direct flights between Bangladesh and Pakistan resumed after more than a decade

Hasina's continued exile is possibly the other, more serious irritant - in any reset.

"The BNP will have to reckon with the reality that Hasina is unlikely to be repatriated. At the same time, the opposition parties [in Dhaka] will keep up the pressure on the government to press India for her return - it's one of the few levers they have to challenge the BNP on foreign policy," says Pattanaik.

It is not going to be easy.

Thousands of Awami League rank-and-file members have reportedly crossed into India after the 2024 July uprising.

"If Delhi seeks to rehabilitate the Awami League from its soil, it will be fraught - Hasina's pre-election press conferences [from exile] were baffling. Unless she signals contrition or steps aside to allow a leadership transition, her continued presence risks complicating ties," says Sreeradha Datta, a professor of international affairs at the OP Jindal Global University.

Then there is the cross-border rhetoric - inflammatory commentary from Indian politicians and television studios that has fed a wider belief in Bangladesh that Delhi sees it less as a sovereign equal than as a pliant backyard.

As Paliwal notes, the "new normal" will hinge on whether Dhaka's new leadership can contain anti-India sentiment - and whether Delhi can dial down its own charged messaging, seen recently in moves such as barring a Bangladeshi cricketer from the Indian Premier League.

"If they fail - wittingly or unwittingly - then the situation will remain in the 'managed rivalry' bucket," he says.

Bangladeshi and Indian cricket fans - sporting ties between the two countries have been hit recently

Bangladeshi and Indian cricket fans - sporting ties between the two countries have been hit recently

To be sure, security co-operation remains the ballast in an otherwise choppy relationship.

India and Bangladesh conduct annual military exercises, co-ordinated naval patrols, annual defence dialogues and operate a $500m Indian line of credit for defence purchases.

"I don't think the BNP will roll back that co-operation. This is a new leader, a different coalition - and a party returning after 17 years," says Pattanaik.

For all the turbulence, geography and economics bind the two: a 4,096km (2,545-mile) border, deep security and cultural links. Bangladesh is India's biggest trading partner in South Asia, and India has become Bangladesh's largest export market in Asia.

Estrangement is untenable - but the frayed ties still demand a reset.

"India's past relationship with the BNP is complex and marked by mistrust more than understanding," says Paliwal. "But given the geopolitical circumstances today, the fact that Rahman has shown political maturity to not let the past become an enemy of the future, and that Delhi is open to pragmatic engagement are promising signs."

The question is who moves first.

"India should take the initiative as the big neighbour. India should do the outreach. Bangladesh has held a robust election; now engage, see where we can help. I'm hopeful the BNP has learnt the lessons of the past," says Datta.

In other words, the reset may depend less on rhetoric and more on whether the bigger neighbour chooses confidence over caution.

After the landslide: Can India

A reset of the frayed relationship is possible, say analysts. But it will require restraint - and reciprocity.(2 )Readerstime:2026-02-15

On TikTok, we're all Chinese –

Chinamaxxing is adding more gloss to the recent flourish of Chinese soft power.(2 )Readerstime:2026-02-15

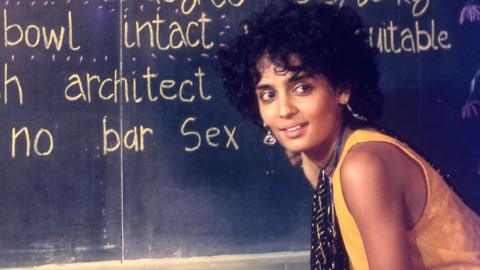

Why writer Arundhati Roy's cul

Nearly 40 years on, the Booker prize-winning writer‘s debut campus satire is set to be screened in Berlin.(2 )Readerstime:2026-02-14

Can Bangladesh's new leader br

Tarique Rahman is set to be Bangladesh‘s next prime minister, 18 months after mass protests ousted its longest-serving leader.(2 )Readerstime:2026-02-14Thai police arrest gunman afte

The suspect has been detained and all hostages freed after a two-hour standoff at a school in southern Thailand, police said.2026-02-11

The suspect has been detained and all hostages freed after a two-hour standoff at a school in southern Thailand, police said.2026-02-11Naan: How the 'world's best br

Naan, a leavened flatbread, was once the food of nobility but is now a global culinary delight.2025-12-30

Naan, a leavened flatbread, was once the food of nobility but is now a global culinary delight.2025-12-30S Korean crypto firm accidenta

The company quickly realised its mistake and managed to recover virtually all the missing tokens from customers.2026-02-07

The company quickly realised its mistake and managed to recover virtually all the missing tokens from customers.2026-02-07Japan has given Takaichi a lan

Japan has been battling sluggish growth, mounting public debt and a rapidly ageing workforce.2026-02-10

Japan has been battling sluggish growth, mounting public debt and a rapidly ageing workforce.2026-02-10